by Evan B. Howard

Every night, people–many people in Colorado–try to sleep outside. Homelessness is a simple fact, not only nationally, but also locally. Let’s take Denver, for example. No matter how you do the math–counting homeless persons and shelter beds available–there are at least a thousand people every night who must sleep outside in Denver.1

Most of us do not really notice many of our simple acts of physical survival. We pull up the covers when it gets cold. We get up and relieve ourselves in our bathrooms, rooms which we also use for hygiene purposes. We prepare our meals in kitchens and eat them in dining rooms. We store our possessions in houses or apartments. But what if we do not have access to these rooms, these “private” places? If private places are unavailable, we are obliged to perform these basic acts of survival in “public” places. We sleep on streets or under bridges or in a vehicle, near to light if possible to ensure safety. If commercial establishments allow only customers access to restrooms, we are obliged to relieve ourselves in alleys. We store (hide) our possessions in a small thicket of bushes in a city park. We gratefully receive food given to us wherever it may be offered. We do what we must to survive.

Most of us do not really notice many of our simple acts of physical survival. We pull up the covers when it gets cold. We get up and relieve ourselves in our bathrooms, rooms which we also use for hygiene purposes. We prepare our meals in kitchens and eat them in dining rooms. We store our possessions in houses or apartments. But what if we do not have access to these rooms, these “private” places? If private places are unavailable, we are obliged to perform these basic acts of survival in “public” places. We sleep on streets or under bridges or in a vehicle, near to light if possible to ensure safety. If commercial establishments allow only customers access to restrooms, we are obliged to relieve ourselves in alleys. We store (hide) our possessions in a small thicket of bushes in a city park. We gratefully receive food given to us wherever it may be offered. We do what we must to survive.

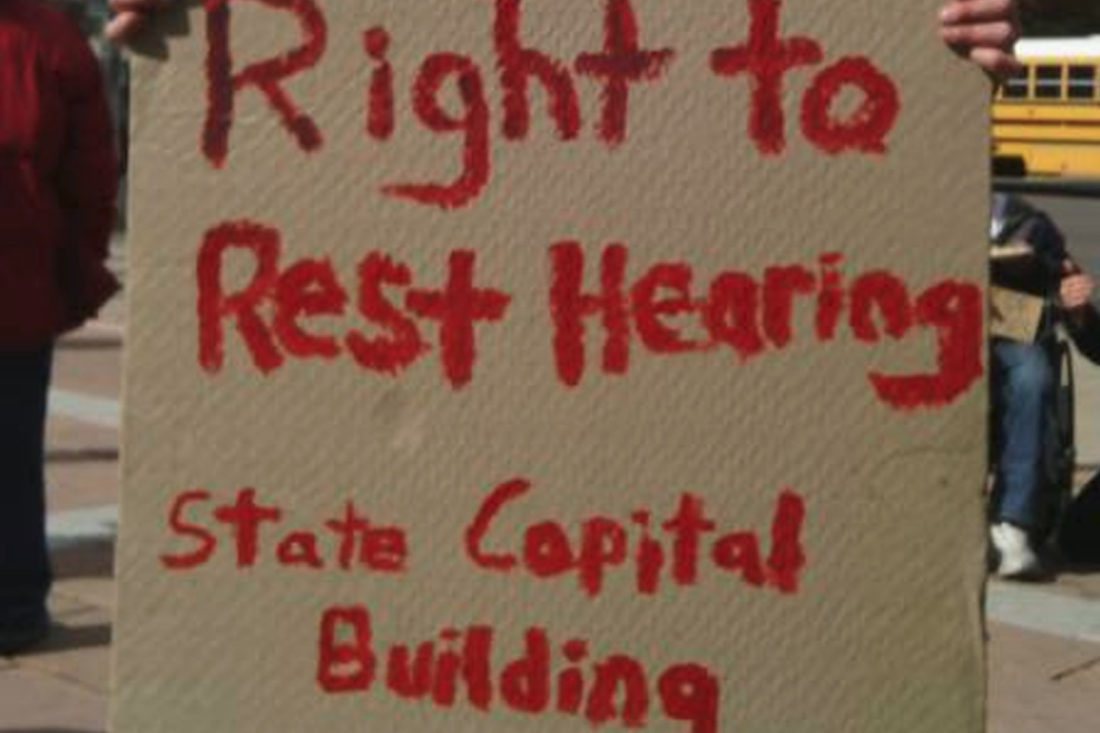

Yet most of these acts of survival are illegal in Colorado. It is illegal in many cities to lie down and cover oneself with a blanket at night outdoors or to sleep in a vehicle. The worldly possessions of homeless persons–wallets, important papers, and more–are regularly confiscated, often in the presence of the owners, and thrown into dump trucks. People have been arrested for indecent exposure while relieving themselves in alleys. In some cities, it is illegal to offer food to a number of homeless people in public parks.2 The passing and enforcement of laws prohibiting these basic acts of human survival functionally criminalize the fact of being homeless. “Homeless rights” proposals, like the Right to Rest Bill up for consideration in Colorado,3 work to decriminalize personal survival in public spaces and give homeless persons an opportunity to live a reasonable life.

I believe that we Christians have a responsibility before God to support homeless rights. In light of the current situation, our approach to the homeless must not be merely an expression of compassion, but must also be a pursuit of justice. Let me explain.

First, God is concerned about giving people homes

From the first chapters of Genesis to the last chapters of Revelation, we see a God who is interested in giving people a home. God places Adam and Eve in a cozy garden. God leads Abraham to a new home in Canaan. God delivers Israel from the hand of the Egyptians, leads them through the wilderness (forty years of portable tent-city living!), and establishes them back in their home. Psalm 68: 6 declares that God, “gives the desolate a home to live in.” Finally, in the book of Revelation we share in the excitement of the fulfillment of history as humanity proclaims, “See, the home of God is among mortals.” The heart of God is to provide security, community, and an environment where humans can thrive in the midst of ordinary life.

Indeed, this sense of the value of “home” is so strong that the choice of Jesus and the apostles to live as itinerant ministers is described as a deprivation of normal life. Thus Jesus warns those who might choose to follow him without considering the costs carefully, “The foxes have holes and the birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay His head.” (Matthew 8:20 // Luke 9:58). The apostle Paul describes the conditions of his missionary work similarly: “To this present hour we are both hungry and thirsty, and are poorly clothed, and are roughly treated, and are homeless.” (1 Corinthians 4:11). Homelessness in Scripture is here described as a voluntary deprivation. God’s desire is that people have a “place” to live.

This is why offering hospitality to people experiencing homelessness is praised in Scripture. Isaiah 58 describes the “fast” that God highly values:

6 “Is this not the fast which I choose,

To loosen the bonds of wickedness,

To undo the bands of the yoke,

And to let the oppressed go free

And break every yoke?

7 “Is it not to divide your bread with the hungry

And bring the homeless poor into the house;

When you see the naked, to cover him;

And not to hide yourself from your own flesh?

8 “Then your light will break out like the dawn,

And your recovery will speedily spring forth;

And your righteousness will go before you;

The glory of the Lord will be your rear guard.

Likewise, Jesus praises those who visit him in prison, or feed him when hungry, or welcome him when he is homeless proclaiming that “just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40).

God is the loving Father who makes a home for the people of his creation and who desires that we follow his example in offering hospitality to others who may not have homes. And indeed, Christians have led the way in providing shelters for people suffering without a place to sleep.4 But I believe that we must take a further step.

Second, God is concerned about justice, about human beings providing one another fair access to the basic needs of human life.

Christian care is not merely a matter of visiting the orphan and widow in distress (though it is that; see James 1:27). It is also about advocating for the just treatment of those who tend to suffer under our political and economic systems. Thus the Lord lifts up Josiah as an example, declaring that “”He pled the cause of the afflicted and needy; Then it was well. Is not that what it means to know Me?” Declares the Lord” (Jeremiah 22:16; see also Isaiah 10:2; Amos 5:10-15; Malachi 3:5). God seems particularly concerned that the most needy among us–those with the least power in any given system: the poor, the alien, the widow, and so on–receive fair treatment and that they do not have their basic livelihood threatened by the nature (or abuse) of the social structures of any given culture.

Perhaps a couple of particular laws might illustrate this principle. In Deuteronomy 24 the people of God are instructed that,

“When you make your neighbor a loan of any kind, you shall not go into the house to take the pledge. You shall wait outside, while the person to whom you are making the loan brings the pledge out to you. If the person is poor, you shall not sleep in the garment given you as the pledge. You shall give the pledge back by sunset, so that your neighbor may sleep in the cloak and bless you; and it will be to your credit before theLord your God. You shall not withhold the wages of poor and needy laborers, whether other Israelites or aliens who reside in your land in one of your towns. You shall pay them their wages daily before sunset, because they are poor and their livelihood depends on them; otherwise they might cry to the Lord against you, and you would incur guilt” (Deuteronomy 24:10-15).

So, what is going on here? Here we find someone making a loan, but unable to keep the collateral offered in security of this loan. Why? Is this not unfair for the lender? The point is this: it is one thing to offer a luxury item as collateral for a loan, but it is entirely a different matter to lose one’s very means of survival (a blanket/cloak, the wages for the day). To deprive the poor of their basic acts of survival is to “incur guilt.” This is not just a weakness of compassion, but rather this is a matter of injustice committed to the poor who in the eyes of God has a right to a blanket, to daily wages.

Similarly, a few verses earlier God commands the Israelites that “No one shall take a handmill or an upper millstone in pledge, for he would be taking a life in pledge” (Deuteronomy 24:6). “Taking a life in pledge.” This is the point. A millstone was a family’s means of creating bread. No matter how desperate a poor person might be, we are unjust when we deprive another of the possibility of fulfilling their basic acts of human survival.

Conclusion –

God created human beings in his own image. Human beings are the peak of God’s creative work. As such all human beings are worthy of treatment with dignity. If an artist were to make a magnificent vase–very beautiful and very delicate–and place it upon a mantle, we would be offending the artist to roughly grab the vase off the mantle and toss it around carelessly. To mistreat the artist’s precious creation is to violate one’s relationship with the artist. And so it is with God. Why have we claimed that slavery is wrong? It is a violation of the dignity of a human being and as such it is a violation against the God who made us.

To make it a crime for a family experiencing homelessness to cover themselves in the cold, for someone to seek shelter in their vehicle, to sit or lie down in a public space when they have no reasonable access to private spaces, to have their belongings thrown away as “encumbrances” is itself a crime against the heart and laws of God. And just as William Wilberforce and John Woolman followed God by advocating for the rights of slaves to the freedom to make a life for themselves, so I believe we must, as Christians, support the rights of people without housing to perform–and thus to decriminalize–the simple acts of survival that most of us perform in our private places, but that homeless people are obliged to perform in public places.

There are many issues I have not addressed in this brief argument. The relationship of shelters and services to “rights,” the issue of employment and many other questions need to be explored and have been.5 I will address one issue in the “Few Thoughts” that follow. My hope is that through this essay we can view homeless people and their plight with the eyes and heart of God.

A Few Thoughts on Love, Incentive, and Change in Homeless Law

(see also https://coloradohomelessbillofrights.org/about/r2r-faq-3/)

After some consideration, it seems best to offer a few responses to a concern I have heard frequently regarding the Right to Rest Act and other similar “homeless rights” bills. I hear this concern raised by caring, compassionate, Christian persons, often people involved at some level in providing services for those in need.

Their concern is that if Colorado (or other states) were to pass a Bill legalizing outdoor sleeping, panhandling, and so on, this would simplyprovide reinforcement to homelessness and not give sufficient incentive toward positive change. The point of this concern is that perhaps in our efforts–through passing a Right to Rest Bill–to help people experiencing homelessness we might be inadvertently harming them. The passing of this Bill would make it all the easier for people just to stay on the streets and not take the steps needed toward a better life. In effect, perhaps our motive of love is well-meaning but misguided: we are not really supplying what is needed most. This is an important concern, deserving of careful reflection. Just what are the best ways of caring for those in our communities that struggle to meet their basic needs? In what follows, I offer a few thoughts as a thinking Christian on this question, particularly in light of the advisability of passing a Right to Rest Bill.

1. The Bible simply encourages us to meet needs.

Christian Scripture, when it urges us to care for needs, actually speaks very little of reform. Instead, it simply urges us toward heartfelt compassion and structural justice. The passages I mentioned in my earlier reflections on homeless rights may be used as examples. Consider Isaiah 58. It does not say, “This is the fast that I choose, to compel the hungry to find jobs, to urge the homeless poor to deal with their addictions so they can have the stability to afford rent, to teach the naked to sew their own clothes.” No, Isaiah simply exalts the simple acts of meeting basic needs. Similarly, Jesus (in Matthew 25) praises those who simply feed, visit, or offer hospitality.

Christian Scripture, when it urges us to care for needs, actually speaks very little of reform. Instead, it simply urges us toward heartfelt compassion and structural justice. The passages I mentioned in my earlier reflections on homeless rights may be used as examples. Consider Isaiah 58. It does not say, “This is the fast that I choose, to compel the hungry to find jobs, to urge the homeless poor to deal with their addictions so they can have the stability to afford rent, to teach the naked to sew their own clothes.” No, Isaiah simply exalts the simple acts of meeting basic needs. Similarly, Jesus (in Matthew 25) praises those who simply feed, visit, or offer hospitality.

In those passages that regulate the procedures for making pledges (for example, Deuteronomy 24:6-15) the point is simply the injustice of withholding the means of survival from those in need. There is no discussion in these passages of the value of assisting those in need of a loan with their finances to better manage their money. But neither is offering a loan (rather than simply offering charity) condemned. Charity and development are encouraged elsewhere.

Here the point is that we are not to arrange our economy such that it endangers the basic needs of populations on the margins.

My conclusion from this is that while social improvement may be a worthy activity, it does not trump God’s desire that the basic needs of those most vulnerable be secured through justice and charity. I heartily support our efforts to provide education, mentoring, rehabilitation and the like. These are good things. But incentive for improvement must not be provided by criminalizing basic acts of human survival or depriving those most on the margin from their basic needs. This is not the love of God.

2. Loving care for those experiencing homelessness requires that we respond out of a sensitive understanding of the complexities of their situations.

A number of years ago I visited a team of Christians working with homeless persons in a large American city. I shadowed them for a week or so, asking questions about their ministry and the people for whom they offered care. This visit confirmed what can be read in the point-in-time counts and surveys of homeless populations all over the country: while many people are homeless simply because of one or another factor that has brought them on “hard times,” there remains a segment of the homeless population whose lives are characterized by the simultaneous presence of a number of complications (for example lack of education, past experience of abuse, psychological difficulties, lack of employment history, substance addictions). Further, this nexus of complications makes it extremely difficult for some to become capable of living in housing as our contemporary society has designed it.

While not every homeless person suffers under the weight of all these factors at the same time, what is the case is that there are a number of homeless persons who suffer under a number of these factors simultaneously. Just the presence of any three of these factors makes change extremely difficult. So, what does it take to maintain oneself in housing today? – “In Denver, for example, if a person worked full-time at an entry level job (making minimum wage), they would clear $1280 after taxes. If they rented a 1 bedroom apartment at the average Denver rental rate of $1244, they would be left with $36 for the rest of their living expenses. It is simply impossible to maintain a life with such tight financial margins.

What this means is that people will be unable to maintain housing and must therefore conduct their survival activities in public space. Currently those of us who do so are treated as criminals for this activity. I believe a state law is needed to protect these peoples‘ need to exist in public space, even while we work to provide affordable housing opportunities and compassionate assistance. The Right to Rest Bill is–from this point of view–not a misguided incentive for people to remain homeless, but rather passing this Bill is an an act of compassion and justice for those who are more likely in contemporary society to be homeless.

3. Establishing and enforcing laws which criminalize basic acts of human survival is a poor strategy for facilitating life improvement

I offer here just a couple of thoughts about using laws against particular survival activities as incentives for life improvement. First, is this really the best means of connecting people with (limited) programs and services? I think not. If the goal is to help connect those needing mental health or other such services with resources designed for those services, this could be better done by hiring social workers to connect with people on the streets. I have been a caseworker for a social service agency. From my own experience, regulations might compel compliance, but it does not always produce sincere change.

The vast majority of homeless persons would prefer to live in homes. Yet, when the federal government stopped funding new public housing–spending dropped from over $16 million per year in 1978 to nothing since 1996–homelessness tripled or quadrupled in every major U.S. city and has risen steadily since. Sufficient housing is simply not available. Homelessness is not just a personal issue, it is a structural issue.6 The conditions of homelessness themselves are incentive enough to produce the desire for change. Many people are afraid of sleeping outside and choose to sleep in shelters whenever possible. Others, however, sleep outside rather than in a shelter because there are not nearly enough shelter spaces for all who need them. Many people with mental health conditions are unable to tolerate shelters. Many are fearful of the bugs, violence, theft, and unsanitary conditions which they often associate with shelters. Furthermore, some persons experiencing homelessness do not need “services.” For example, over 30% of those surveyed in Denver stated that they have been employed within the past 30 days. It is extremely hard to find or keep a job while living in a shelter and with no place to store your belongings and no way to afford transportation. Many shelters require you to “show up” at times that are inappropriate for your employment. Or perhaps you are married and choose not to live in a shelter because you want to maintain your marriage (a one– or two–night emergency is one thing — a lifestyle of shelters is another). For these persons, laws which make it illegal to cover oneself at night, to sleep in a vehicle and the like, function not as positive incentives for life improvement but rather as roadblocks to life.

Conclusion

So what is the best way to love people experiencing homelessness? How can we order a society that best reflects the kind of values that our God would desire? And what might this vision have to do with a Right to Rest Bill? I think I go back to the second great commandment: “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:27). Persons experiencing homelessness are our neighbors. That, in part, is the point. They are our neighbors in public spaces everywhere. Indeed, I felt a bit uncomfortable describing the complications of homeless people as “they.” “They” are our neighbors. It is not really a matter of how “we” treat “them,” but of a fresh realization of who “we” are. Jesus brings this home again and again.

How I treat “them” (“the least of these”) is how I treat Jesus.

How I want to treat “me” is how I should be treating “them.” When I look at “them” through the eyes of “me” in Christ it all becomes a matter of a wide-reaching “we.” What would we want if we were faced with the problems and the resources available to homeless persons today? I think we would certainly want compassionate encouragement toward self-improvement rather than a command to move along because we were illegally sleeping in my only safe location. We would certainly want to know about available housing that is appropriate to our circumstances rather than being forced from our vehicle. We would certainly appreciate a hand up if we wanted or needed one. But this hand must be a hand of understanding, not a hand of condemnation and criminalization. Consequently, I think one excellent way to love my homeless neighbor as myself is to offer my public support to the Colorado right to Rest Bill. This would make God very happy.

About the Author

Evan B. Howard, Ph.D. is the founder and director of Spirituality Shoppe, a Center for the Study of Christian Spirituality. He is affiliate associate professor of Christian Spirituality at Fuller Theological Seminary and teaches at other institutions. He is the author of The Brazos Introduction to Christian Spirituality and leads workshops and seminars on Christian Spirituality worldwide.